This post is based on a roundtable discussion I participated in at the 2015 African Heritage Studies Association Conference in New York City, NY. My oldest son, Akil Parker, was also a member of that panel speaking on his experience as a math teacher.

Introduction

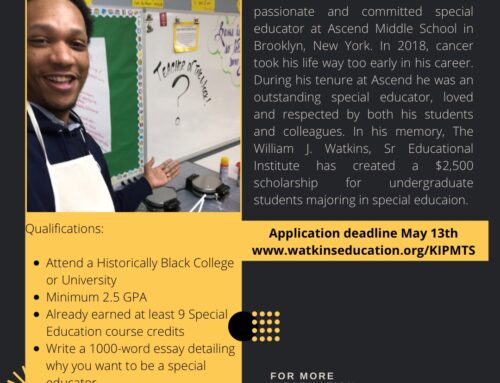

This paper is a reflection on my more than 30 years of working as a public school educator in New York City Public Schools, Baltimore City Public Schools and Baltimore County Public Schools. I spent the vast majority of my years as a Social Studies teacher and Department Chairman. I also worked as an Assistant Principal in a comprehensive high school and Principal of an Evening High School. But, for most of my career I was a classroom teacher working directly with young people on a daily basis. I retired from the Baltimore County Public Schools in 2014 and began building The William J. Watkins, Sr. Educational Institute. Our mission is to ensure that ALL children receive the best education possible; especially those in under-served and under-resourced communities. During my career as a public school educator my area of focus was and continues to be African American History. I have earned a masters degree in African American Studies and a doctorate in History with a concentration in African Diasporan History, both from the prestigious history department at Morgan State University. My dissertation is an educational history, Selected African American Educational Efforts in Baltimore, MD during the 19th Century. One of the questions I wanted to answer was “Were Black schools really better before integration?” I heard this exclaimed many times and wanted to really do the research to see if it was true and, if so, why? As I assumed, the answer to the first part of the question was yes. African Americans did receive a better education and did better in school before desegregation.

Historical Context

The answer to why we did better is the focus of my reflection here. I found that in the African American community education was arguably the most important source of cultural capital. As cultural capital it created a shared identity and served a common purpose, obtaining spiritual freedom, ending slavery and later, gaining acceptance into the American body politic. These goals were achieved through teaching African American History. Students were inspired by teachers who built upon the challenges that earlier generations had overcome and encouraged them to uplift the community further. In essence, they were nation building.

Desegregating the public schools had a number of unintended consequences. Arguably, the most debilitating impact on the African American community was that it was no longer in control of the education of its children. The separate school “systems” that were established were at least nominally controlled by the African American community and the teachers in the schools were, for the most part, members of the African American community creating cultural capital and teaching for liberation and uplift. With integration, those school systems were dismantled, many of the teachers removed and control of our education was swallowed up in the mainstream narrative of the “American dream.”

This was challenged in the 1960’s and 70’s by the Black Studies Movement. The push for Black Studies and African American History in American colleges and universities was an attempt to empower African American college students through creating the same type of cultural capital that was generated in the public schools prior to integration. One can argue to what extent it has been successful. On the k-12 level the Black Studies Movement was much slower in taking root. When I entered the teaching profession in the early 1980’s there were remnants of the gains of the Civil Rights and Black Studies movements present. I remember finding books in the Morris High School library in the south Bronx that would have made Carter G. Woodson proud. But, they had not been used in years. I was scheduled to teach a course in the history of “Black New York.” There were no curricular resources, textbooks to speak of or support from the Office of Curriculum and Instruction. I was left to teach the course on my own. Which, was actually fine with me. I had the freedom to teach whatever I wanted to teach. The course was a “dumping ground” for students with holes in their schedules and problems for other teachers. Left to my own devices I began the process of building cultural capital and teaching for liberation with the students that did not matter to the New York City Public School system. Precisely the students who needed the course the most!

So, where are we today as far as teaching African American History in the k-12 universe goes? The short answer is, far from where we need to be. My objective here is not to give an exhaustive history of how African American History courses have developed in American public schools but rather to share my experience as a public school educator for more than three decades teaching African American History, writing African American History curricula, training and supervising teachers. The first question that must be addressed is what is the purpose of an African American History course in a k-12 setting? The early attempts to develop African American History curriculum in the post-desegregation era were driven by protests that argued for inclusion. Such efforts as the Portland Oregon school districts Multicultural Baseline Essays collection that were created in the mid-1980’s is an example of this effort. The essays were lauded for their broad approach to providing educators with content to craft inclusive instruction. Asa G. Hilliard, III consulted with the Portland School System on the creation of the essays.

Later, and in response to these inclusive efforts, were efforts to create an historical narrative that challenged the accepted American historical narrative. Such efforts also included a strong focus on African identity. Molefi Asante’s works on Afrocentricity and his high school textbook, African American History: A Journey of Liberation, exemplifies these efforts. Most of the school districts that have implemented or created an African American History curriculum have been compelled to do so either by political pressure or community activism.

Doing the Work

The main reason I was recruited to teach in Baltimore County Public Schools was because students at one of the local high schools, Woodlawn High, at which I later became an assistant principal, protested to the school system about the lack of an African American History course. This was in the late 1980’s. It wasn’t until 1991 that the first course was offered. I piloted the curriculum at Randallstown High that year. The course was a half credit, one semester course. It was designed to cover content from ancient Egypt to modern United States History! While its goals were laudable the breadth was too much for one semester. During the years that I taught the course I reorganized it, sometimes by themes and at others by topic. I once designed the course based on the theme of resistance. We examined different ways in which African Americans resisted oppression throughout our experience in America. I focused on such topics as slavery and the modern civil rights movement. No matter what approach I took I would do an overview of the historical periods in the African American experience in the United States. I attempted to implement the curriculum in such a way that my students, the majority of which were African American, were able to create a worldview that was relevant to them and their historical experience in order to inspire them to contribute to the uplift of the community and to seek social justice. This is the same tradition of those who taught in the “Colored” schools prior to desegregation. Further, this is the type of African American History curriculum that needs to be developed and implemented. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons such curricula do not exist.

One of the main reasons such curricula do not exist is because the historical narrative challenges not only the dominant American historical narrative of rugged individualism and American exceptionalism, it directly challenges white supremacy and institutional and systemic racism. For school districts and state departments of education to even begin to consider writing an African American History curriculum that empowers ALL students in this way they would have to wrestle with the difficult issues of race and the truth about not only United States History but World History. Therein lies the challenge. The will to address these issues just does not exist in the vast majority of curriculum offices throughout the school districts and departments of education around the nation, even those controlled by African Americans.

Another challenge to creating an empowering African American curriculum is the differing views on the purpose of education. Historically, the limited amount of education deemed necessary for African Americans was just enough to execute the menial low paying jobs reserved for African Americans. Today that minimal education has become just enough to keep African Americans out of jail and off the public assistance rolls. The African American community, on the other hand, sought an education that at its very core led to freedom and to fulfill their human potential.

Many of the problems that teachers face today are precisely because schools do not address the need to have an education that is empowering to African American students. Public education systems are not designed to provide such an education. Their focus is on job creation. For them the purpose of education is to get a good paying job, become a responsible citizen and pay taxes. For us, education must serve a much higher mission.

There is also a lack of expertise in African American History at the highest levels. While many curriculum writers, directors and supervisors are well versed in pedagogy and other areas of history very few have the content knowledge to create meaningful African American History curriculum. In order to get those with the expertise and ability to write such curriculum it is a very costly venture requiring outside resources. This was the case when I worked with the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE). The MSDE has a statewide African American History curriculum for secondary students. I worked on this curriculum from its beginning as a writer, reviewer, pilot teacher, trainer, member of the task force and I currently serve on the advisory committee. It is a partnership between the Reginald F. Lewis Maryland Museum of African American History and Culture (RFLM). The curriculum was primarily funded by a gift from The Reginald F. Lewis Foundation. The funding supported teams of curriculum writers, workshops, writing, reviewing, piloting, publication and teacher training to get the curriculum into the schools. While the partnership was much needed and successful, without the major funding from The Reginald F. Lewis Foundation, the MSDE would not have acted on its own to commit the resources necessary to bring the curriculum to life. I do applaud the MSDE for assigning a dedicated staff person as a liaison to the RFLM to spearhead an advisory committee to further the development and implementation of the curriculum. But, the fact remains that the MSDE had not acted to create a curriculum in African American History since the department was created in the 19th century.

On the school level you have similar challenges when supervisory personnel lack the knowledge and understanding of African American History. For instance, I was once challenged by a department chairmen and principal for showing the film Sankofa in a world history course during Black History Month. They could not understand how using the film was an appropriate resource in teaching about slavery! The department chairmen was in the classroom when the scene where Shola was branded was playing. The concern he brought to me was that parents would be upset because of the nudity. His lack of understanding of the widespread knowledge of and acceptance of the film in the African American community caused him to overreact. This incident occurred after more than a decade of using the film in my world, United States and African American History courses. Their ignorance of how appropriate and successful an instructional resource was and had been in my courses for more than a decade illustrates the challenges faced by educators who are dedicated to empowering ALL students with the knowledge and tools necessary for the development of a worldview that is relevant and empowering.

Further exacerbating the problem is that even where curricula exist too often teachers do not have the requisite knowledge or expertise to teach it. Going a step further, many of the courses that do exist are elective courses and consequently are often not offered to students because of the lack of properly prepared staff to teach the courses and/or scheduling challenges. So, in many schools that are populated with African American students the very course that is central in not only their success in school but in life is not even offered!

Moving Forward

So, then how do we address these challenges in the current state of affairs? The most ideal situation does not exist and will not exist for a very long time. That ideal situation is where the African American community has the capacity to create and operate systems of education for ourselves with the purpose of empowering our children to be free, to build a world that ALL can live in peace and prosperity and to achieve their highest human potential. Most of the children in our community attend some manifestation of public schools whether they be chartered or operated by a public school board. So, we must exert as great an impact as we can on how those institutions operate. I have several recommendations based on the current status quo and how to change it to the ideal situation described above.

First, we – African American educators with the knowledge and expertise, must create an African American History curriculum we want our children to learn that attend public schools. That curriculum must be based on a different narrative than the mainstream American historical narrative. In fact, it must challenge that narrative if it is to truly be liberating. Second, we have to develop a set of standards by which we can assess and evaluate the curricula that already exists and to ensure those that are created in the future serve our purpose of education for liberation. Thirdly, the curriculum and standards creation must be a collaborative process open to input from African American organizations, institutions and individuals whose goals are to liberate and uplift our community.

Once the curriculum is created we will still face the challenge of implementing it effectively. In order for the curriculum to be effectively implemented we need knowledgeable and skilled professional educators at all levels. Thus, we must encourage our best and brightest to become educators and support those who are already in the trenches. We have to create professional development and accreditation processes to develop and enhance the knowledge and skills of our current and future teachers.

Further, we must push to make African American History a mandatory high school graduation requirement. There are several school districts that already have such a requirement. In both Philadelphia and the state of Florida African American History is a high school graduation requirement. However, the Florida model falls short in that it is an infusion model where the African American experience is infused into existing courses through a humanities approach. Philadelphia was the first, and I believe, is the only school district that mandated a specific high school course in African American history as a requirement for ALL students in order to graduate from high school. In both instances these mandates were put into place through political pressure. The strategies used in these instances need to be examined and replicated in other jurisdictions. However, these districts are still faced with the challenges of properly trained and capable staff to implement the curriculum.

Our current institutions must be supported in the ongoing process of revision, development and training. HBCU’s should be in the forefront of this effort. Our schools of education and history departments should be collaborating on creating courses of study that prepare new teachers, in a very purposeful and intentional way, to be creators of the cultural capital that will empower and liberate our youth.

Finally, we must also create new institutions that garner the vast technological and information resources of the 21st century to do the same. We must harness the tremendous capacity and potential of the new instructional technologies to train our educators and deliver the most engaging, vibrant and contemporary lessons possible.

Final Thoughts

Throughout my years of service as a public school educator regardless of what capacity I served in I always saw myself in the position of being an oasis, especially for African American students. In our public schools African American students are often marginalized, misunderstood, devalued, ignored and disrespected. I always made myself available for my students and created space for them where they knew they were valued and respected; where their voice could be heard and they could freely and openly express themselves. Whether by advising the Black History Club or the Muslim Students Association I ensured that our children received the best education possible and that they were not cheated or left out. Until we have our own school systems and are in full and complete control of the education of our children those of us who serve in public education, particularly in schools that treat our children as if they do not matter, we must serve as oases for them. We must support, encourage and empower them, in spite of the challenges we are confronted with as professional educators. We must navigate the highly charged political landscape and be “the spook who sat by the door” constantly building!

Concomitantly, the African American community must re-focus our priorities and make education a source of cultural capital again. Education should serve as a tool to create a shared identity and communal purpose of uplift. Those who are engaged in this process should be upheld as role models and pillars of the community not athletes and entertainers. As a people, we have replaced education with gross materialism, conspicuous consumption and immediate gratification as our cultural capital. Instead of education serving as a means to fulfill our highest human potential and to gain freedom we have used it as a means to achieving the American dream. For too many of our children in public schooling, they know that dream is unattainable and not meant for them to realize. Thus, when they enter the schools and all of its components from the condition of the buildings to the attitudes of the teachers tells them that they don’t matter, they are turned off from education. When we restructure our community focus on the true purpose of education, then, when our children enter our schools they will know that they are valued and that they have a purpose and role to play in the freedom and uplift of themselves, our community and the world.

Leave A Comment